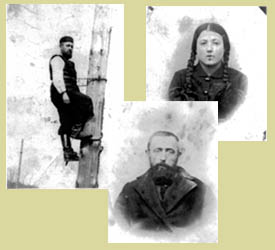

Grandfathers Moshe and Yosef, and aunt Malka

Just as the train was about to pull out of the station, a young woman nearly fell out of her cabin’s window as she leaned out, screaming frantically, “Give me back my baby! I want my baby back!” Her outstretched arms beseeched the elegant couple bidding her farewell from the train’s platform — her brother and his wife, an infant cradled in her arm. “Give me back my baby! I want my baby back!” The train was starting to chug out of the station by the time her brother and sister-in-law found it in them to comply. Tearful and out of breath, they passed the newborn Malka through the speeding train window to her mother’s arms.

Had it not been for her mother’s last-minute change of heart, Malka would most likely have been another child among the millions of children exterminated during the Holocaust, where nearly all the members in her family perished, including the uncle and aunt who had wanted to adopt her.

Father Israel in early pioneering days

The irony is: Even when she was screaming, “Give me back my baby!” at the train station, Malka’s young mother believed, as did most everyone in her extended family, that her newborn daughter would be safer in Europe than in the Middle East, where she was heading. Israel at that time existed only in the realm of dreams dreamt by idealists like Malka’s mother and father. Fully aware of the danger and hardship inherent in pioneering life, they had thought their newborn Malka would have a better chance to survive in Europe.

From that window of that speeding train to the tent flaps in the Sinai desert, Malka Marom has entered life through whatever opening or crack destiny has offered her.

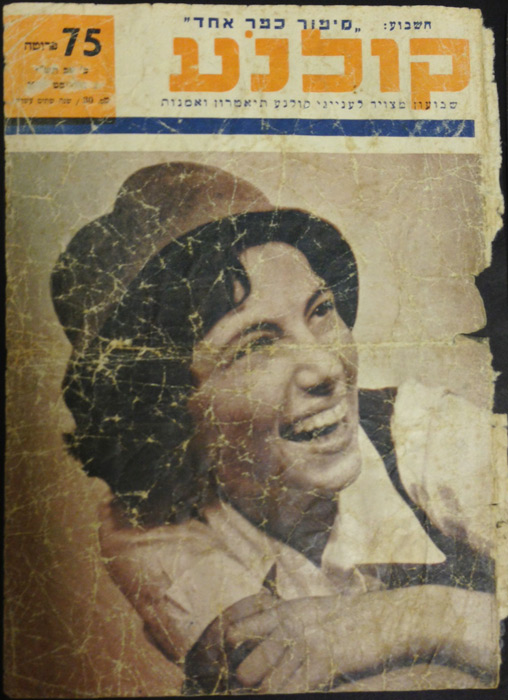

On cover of Kolnoa movie magazine

As a child she was picked to play a leading role in the first movie filmed in Israel — merely a fundraiser, yet such a first: Steven Spielberg chose to house it in his archives, and when it first came out, Malka was featured on the cover of Movie Magazine and accorded favourable press reviews.

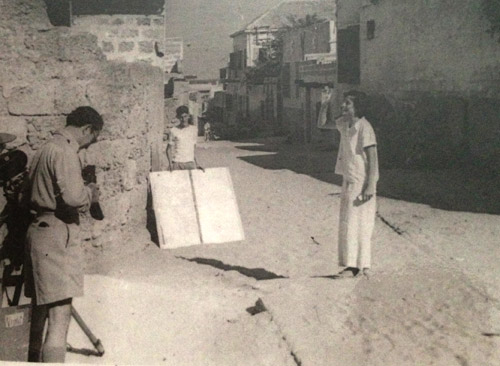

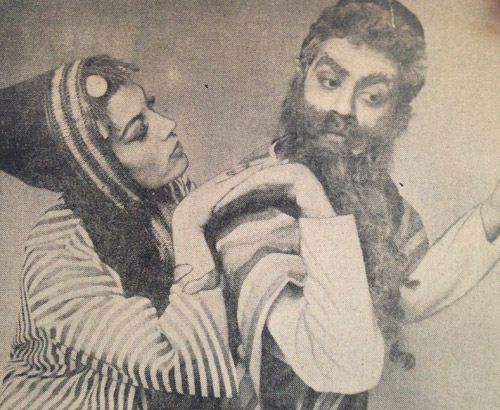

On the set of A Village Tale

In her early teens Malka participated in the Dalia Festival, where the creation of what today is considered Israel’s folk songs and dances took place.

While still in her teens Malka left her studies at the Seminar Lewinsky in Tel-Aviv a year before graduation, to marry a Canadian and move to Toronto.

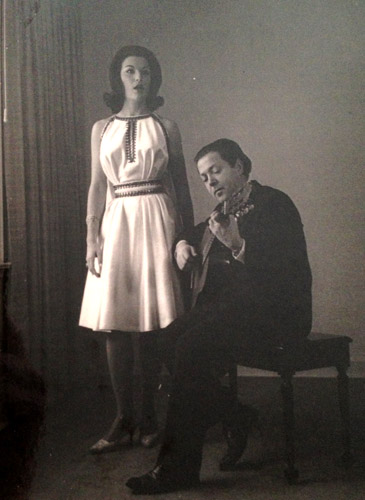

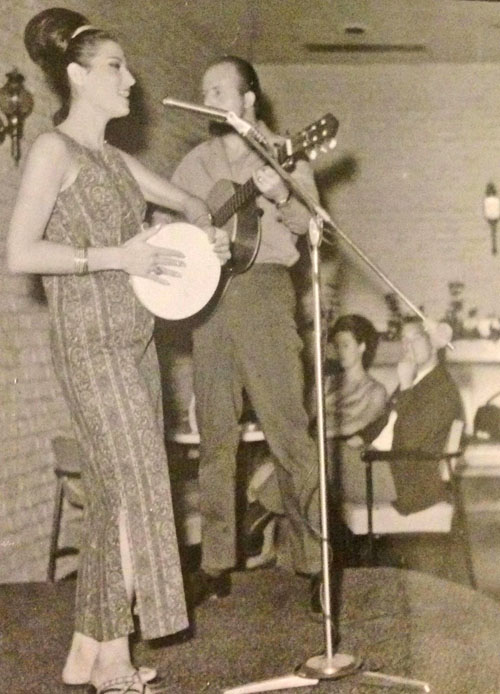

With master guitarist Eli Kassner

In Toronto then, World Music was played underground, literally, in basements only, as if it were subversive. World dance and world culture fared no better. It was at the YMHA’s basement that Malka danced and sang during those years. Toronto, not unlike other colonial towns, was more English than the English and quite closed to most anything and anyone outside the confines of English mores. Malka was singing for a dance festival at the Y, when one of Israel’s leading song writers, Amitai Ne’eman, heard her, encouraged her to sing professionally, and offered to mentor her. But it was for the sheer joy of music-making that she rehearsed his songs as well other “world music” in the basement of the master guitarist Eli Kassner (who years later played lead guitar on all her recordings).

As Rachel in Ancient Roots

Malka’s first performance “above ground” was when she danced a lead role in the performance of Ancient Roots (India’s, Bali’s, and Israel’s) at Hart House, a small theatre on the campus of the University of Toronto. The local press accorded her her first recognition and “buzz.”

On tour of North Western Territories

In 1963, she and Joso Spralja formed the singing duo Malka & Joso. For the next four and half years, they sang folk songs of many lands in fourteen languages — well above ground: in Yorkville’s coffee houses, college campuses, supper clubs, radio and TV and Capitol recordings. Long after the duo parted, they’re regarded as a major force in bringing about the change in perception that saw the immigrant, the ethnic, the newcomer, not as aliens, but as importers of vitality, hope, daring, ancient and avant-garde sophistication, humour, and culture.

Malka & Joso

Their first album, Introducing Malka & Joso, recorded by Capitol EMI Canada, and released in both England and the United States, garnered rave reviews and outsold many of the label’s English-language albums.

“At a time when folk singers sang as if detached from their bodies and emotions, Malka & Joso came on the scene oozing sexuality and passion,” recalls the painter Helen Lucas. “Theirs was a partnership that legends are made of.”

“Many of their renditions became classics,” says master guitarist Eli Kassner. “They made an immediate impact on the concert scene and went from success to success to become world famous.”

“In ‘The Great Folk “Scare” of the Sixties,’ Malka & Joso were a rarity among those great artists,” recalls Shelly Schultz, president of the William Morris Agency in New York.

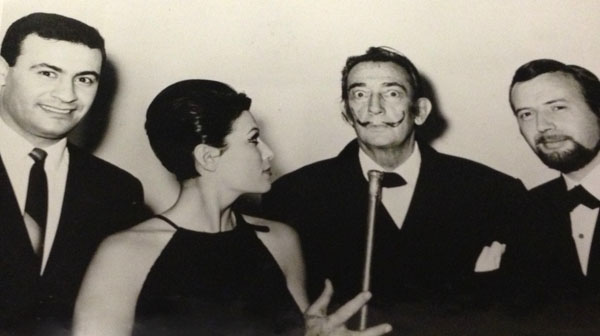

With Salvador Dali, Joso and Nico

Malka & Joso’s second album, Mostly Love Songs, came out in late 1965 — just as the duo won an RPM Award as the year’s Best Folk Group.

Their third album, Jewish Songs, featuring Hebrew and Yiddish songs, proved to be another bestseller.

Their fourth, Folk Songs Around the World, featured the best of the tracks from the Malka & Joso recordings. It was released in Britain, France, Holland, and Italy.

In the fall of 1966, Malka & Joso’s A World of Music TV show followed the Saturday night tradition Hockey Night in Canada. The weekly CBC series took the duo’s international repertoire into the living rooms of the nation. “[Their] show projected an image of cosmopolitanism that is, let me say it, perfect,” said the critic Robert Fulford, in the Toronto Star.

Malka & Joso Forever, a CD retrospective of their songs was released by EMI in 2001 to rave reviews. “Andrea Bocelli could learn a lot from Joso,” declared the Globe and Mail. “But Joso probably would not have been as effective without Malka’s alto sung in such an intimate heartfelt way as to make it seem like the sound of drying salt tears [or] full throated, like a field worker with both feet in the soil.”

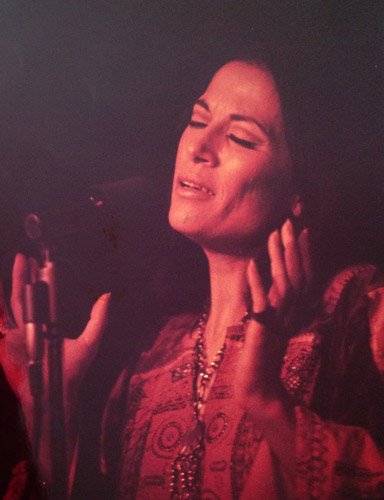

At the Riverboat Coffeehouse

When the Malka & Joso duo dissolved, Malka continued to sing on her own.

On Mosaic TV Show

In between concert tours she wrote, hosted and sang in the weekly CBC Radio program Song of Our People, and the weekly City TV show Mosaic. Later she would host a two-hour CBC showcase of the cultural riches Canada’s immigrants have brought to their adopted country.

From her unique vantage point as the outsider on the inside, Malka interviewed Joni Mitchell on two separate occasions. Her first profile of Joni Mitchell, broadcast on CBC Radio, was nominated for the ACTRA Award. Her two-hour conversation with Leonard Cohen afforded a privileged insight into the mysteries of the creative process and life in music.

With Leonard Cohen

With General Moshe Dayan

Malka’s interview with the legendary one-eyed Israeli general, Moshe Dayan, was broadcast on CBC TV. Her documentaries, My Jerusalem and The Holocaust, received nominations for the ACTRA Award. Her eight-hour radio documentary about the American Dream, The Bite of the Big Apple, earned her not only the nomination for the ACTRA Award, but the prize itself.

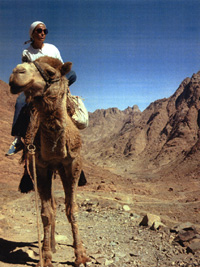

A twist of fate led Malka to the Sinai desert where she recorded her documentary The Bedouins, which won the Ohio State Award, as well as her Desert Diary, which was also nominated for the ACTRA Award.

Holocaust Memorial

At the Sinai Desert

It was during her journey to the Sinai that her novel Sulha was conceived. In the course of the research for her novel, Malka lived in the nomadic tents of five different Bedouin tribes in the Sinai and the Negev deserts for weeks and months at a time. Once, after a three-month stay with the Bedouins, she found herself unable to make the transition back to life in Canada. Living and sleeping by the fireplace of her Toronto home, she cooked over the open fire and brewed tea and coffee as she had been taught by the Bedouins — that’s where she wrote the first pages of Sulha.

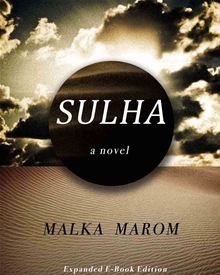

Cover of original print version of Sulha

“The Desert is a place where good and bad are wedded like sun and shade, where a stranger is always received and always shut out, a place where the common language is often silence or guns, where the horizon is wide and the boundaries narrow.” — Sulha

Cover of E-Book version of Sulha

A portion of Sulha won the Ontario Arts Council Award for the most promising work of fiction in progress. Upon its publication in Canada, the literary critics lauded the novel: “Sulha is a splendid hymn to love, dignity, honour and duty. The riveting tale unfolds in what will surely become one of the surprise hits of this literary season.” (Globe and Mail) “In this, the first step of what promises to be yet another distinguished career, Marom has found yet another way to leave her music echoing in our memories.” (Vancouver Sun) “Marom powerfully and lyrically evokes a people and a country in the grip of obsession. The heat and chill, smells and sounds, and paradoxes of the desert mesmerize; sand sifts from our clothes even after the book is done.”(Quill & Quire) “Marom has created something much more powerful and daring than yet another war novel. She has created an original and unforgettable novel of peace.” (Vancouver Courier)

The Nobel Peace laureate Elie Wiesel praised Sulha as “One of the most poignant and inspired novels to have emerged from modern Israel’s harrowing yet exultant experience.” And the Jerusalem Post stated, “Rare in the avalanche of books on the Arab-Israeli conflict, most of which take a stand, Sulha gives every side its say in the infinitely complex situation.” “I refused to make it simple, life is not simple, love is not simple, nor is forgiveness, reconciliation and peace, especially in the Middle East,” Malka said in the Jerusalem Post.

With Joni Mitchell

Joni Mitchell – self portrait

Sulha was published in Canada and also Germany and Greece. An ebook version on the novel is available from ECW Press.

Marom’s next book: Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words will be published by ECW PRESS in 2014. Conversation with Leonard Cohen is slated to be published by ECW PRESS in 2015.

Malka is married and is the mother of Martin Himel and Daniel Marom.