Making of Sulha

The Bedouins manner of opening their hearts and revealing their secrets—not directly but through, poetry, legends, parables and stories—inspired me to seek out my own stories, legends, parables, poetry and secrets; and to examine not only the consequences of history, but also the possibility of transcending them.

The Bedouins manner of opening their hearts and revealing their secrets—not directly but through, poetry, legends, parables and stories—inspired me to seek out my own stories, legends, parables, poetry and secrets; and to examine not only the consequences of history, but also the possibility of transcending them.

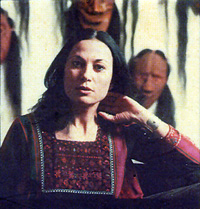

“There was only one paved highway in the whole peninsula in ’78. Every few kilometres south of Eilat, this highway climbed a hill or a mountain, rising so close to the Gulf of Aqaba–Eilat, that when the sun disappeared behind the mountain range west of the highway, the sister range swelled east across the gulf, in Jordan, and farther south, in Saudi Arabia. The faint image of the gulf looked like the creation of an artist who had no desire or time to finish his picture, choosing instead to paint half the gulf on half of the canvas and to fold it precisely while the paint was still wet, in order to press an exact copy.” (Sulha)

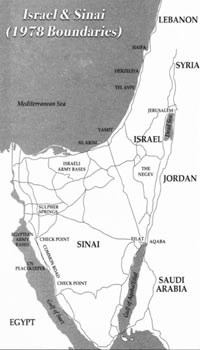

While the map to the right reveals how vast is the expanse of Sinai, especially in comparison to the Negev desert and to Israel, it clearly doesn’t indicate the whereabouts of Bedouins (“real” or fictional) since this was the wish of the Bedouin clans who had offered me not only shelter, food and water for days and weeks that turned into months, but also their songs, dances, poems and legends by fire circles burning long into the night.

Due to my respect for these Bedouins’ wish, this map indicates only the places that Leora and Tal touched during their journey that offer no clue to the whereabouts of the “forbidden tents”. Yet quite a few readers of Sulha’s first trade- paper edition informed me that they figured out the (fictional) location of the (fictional) “forbidden tents” from the grey lines snaking across and around the Sinai and Negev deserts.

In fact, these grey lines attest to the madness that had possessed me to traverse these deserts—along these grey lines and countless more—without knowing why or what for. Nor did I question what compelled me to study Arabic so that I could communicate with the Bedouins without an interpreter and stay alone in their encampments; nor what compelled me to purchase a jeep especially equipped to cross treacherous desert passes, let alone roam by foot for countless kilometres through hostile terrain alone with nomads I’d just happened to meet, all the while snapping hundreds of photographs with three cameras and recording countless cassettes, scribbling observations on heaps of steno pads.

It was a mystery to me, and remained all the more so while this novel was created—or rather, received from a mysterious giver. Or so I felt. By the completion of the novel, I believed that the real stuff had no more to do with anything contrived by me than the grain of sand that forms the windows and mirrors held ever so lovingly, in this novel—to reveal

- the sacred site of memory;

- the heartbreak and the beauty inherent in a culture and a person’s contradictions;

- the Forbidden Other—the Other who affords insight into oneself;

- the hidden connections among most everything—even “arch-enemies”;

- the place that paints in the colours of disappearance the two age-old adversaries: settlers, who aim to reclaim the land, to defend it to the last;

- and nomads, whose relation to the land is much different: they live on it, live off it, move on, and find ways to love the land without becoming bound to it;

- a place where life and death are tightly pressed and constantly bumping and scraping against each other. Like flint stones when one strikes the other, they spark fire, energy, passion, and inspiration, not only of ingenious ways to survive, but also of the prophetic powers and poetry found in the Bible; and the full power of life—of being alive!

It was in this state of being that the idea for this novel came to me all at once, sort of like love at first sight, conception at first try, when you don’t know what it takes to raise a child. I had no idea then that this child would grow up to sing with the exquisite tension created by two opposing pulls: the striving to attain the mythic dream of the New World—the pursuit of personal happiness in peace; and the longing for the mythic long-ago days when the world was a purer place and underneath everything there was a sacredness.

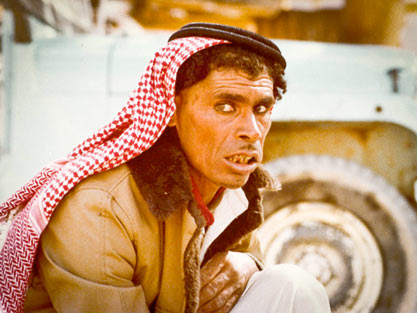

The following photographs were taken during my research work in the desert.

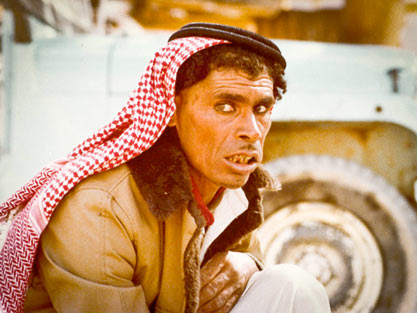

The nomads equipped not only me but also my jeep with amulets to ward off the evil eye of envy (“. . . more graves are dug by the evil envy in men’s hearts . . .” Sulha).

The nomads equipped not only me but also my jeep with amulets to ward off the evil eye of envy (“. . . more graves are dug by the evil envy in men’s hearts . . .” Sulha).

Here from the front seat of my jeep is yet another of my futile attempts to capture the sheer physical and geographical awesomeness inherent in Sinai. The heart yearns for one more try, with this or that lens, only to find it’s impossible for a camera to capture this desert that “shows you a different face every minute, a kaleidoscope of vistas powered by the ever-changing angle of the sun—and of colours. Especially when the slanting sunrays tease colour out of stone. The mountains, boulders and rocks are streaked with ancient hues of bronze and rust, copper green, iron red, yellow, purple and pink, grey and brown, while the sky bands the horizon with cloudless blue.” (Sulha)

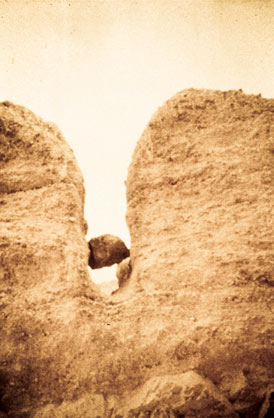

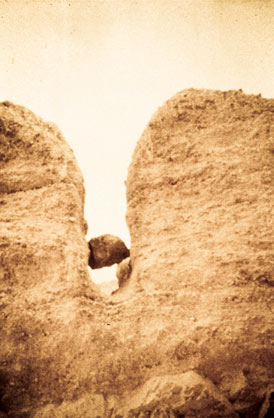

Just a glimpse of how narrow and treacherous are some of Sinai’s wadis—so narrow that even the echo of a whisper trembles and amplifies how deep is this particular mountain fissure, which opens to a different geological era. Way up, the sky is a sliver of blue squeezed between two towering walls. The sun has never been here; the cold and dark are as old as time. In the shade, one can see history in the mountain walls—layers and layers of years, decades, centuries, in countless colours and shades. I could touch time here, polished smooth by flood waters at the top. At the bottom, flash floods must have gushed over the centuries with a force that ripped away mountains along the way—boulders too large to clear this narrow passage.

“What drew you to the Bedouins, of all Arabs?”

“Why did you choose to do a documentary of the Bedouin culture and way of life?”

I’ve been asked these questions ever since my documentary The Bedouins won the Ohio State Award.

Well, to put it bluntly, I was a freelance broadcast journalist at that time, and I figured it would be easier to sell something that nobody else was doing—something that amazed me and troubled me terribly. The Bedouins’ Sinai made all the banner headlines at that time, as it was the subject of heated debates at the UN as a trading chip to facilitate a peace between Egypt and Israel. Yet no mention of the Sinai Bedouins’ rights to their Sinai was to be found in those banner headlines, let alone in the UN debates.

On a practical level, I figured the Bedouins would accept me more than other Arabs, because it’s part of the Bedouins’ way of life to accept guests, all guests, even be they arch-enemies. Hospitality in the desert—at that time—was like the First Commandment.

Deeper still, on the deep-seated emotional level that I’d kept secret since my childhood years, I was extremely curious to find how the Arab nomads lived. Of course, I romanticized it as a child, when it was a life-risking danger to cross the divide between my hometown and the neighboring Arab town only a short walk away from my bedroom’s window. Or so it seemed to my child’s eyes.

Therefore it was like a child-dream come true when the true Arabs (as the Bedouins refer to themselves) invited me to visit-stay with them. It so moved me that I quit my work, left my children, my husband, my parents, and my home to accept the Bedouins’ dream invitation.

Little did I know that after living in Bedouin encampments for months, I’d return home—and what a culture shock that was! I couldn’t adjust even to sitting on a chair. I sat—lived, really—in front of the fireplace in my home. Members of my family were alarmed when they heard my booming voice reduced to a barely audible whisper, as if I were still in a desert that carried even a whisper for miles, and found that there was no persuading me to move from the fireplace in which I cooked and brewed coffee, week after week. I slept by that fire for months. I also started the first draft of Sulha by that same fire.

What’s the difference between the Bedouins’ outlook on life, and ours—the so- called Western outlook on life?

That difference can be put in “a nutshell”: a Bedouin considers his lot in life to be good/fortunate even if nine things out ten are bad, and only one is good. We of the West, however, consider our lot to be unfortunate/bad even if nine things out of ten are good and only one out of ten is bad (for instance, if one’s child “lacks discretion” as the Bedouin refer to a mentally challenged child, a condition which is not uncommon among the Bedouins, due to their age-old custom of marrying their first cousins, as many social scientists maintain.)

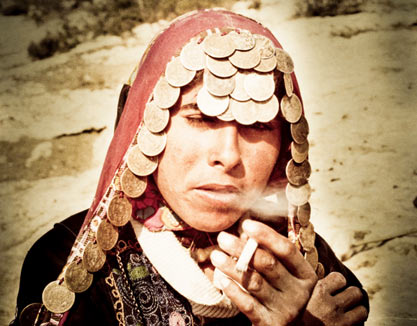

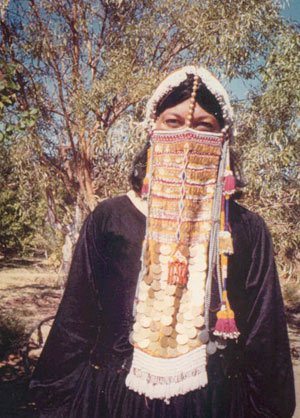

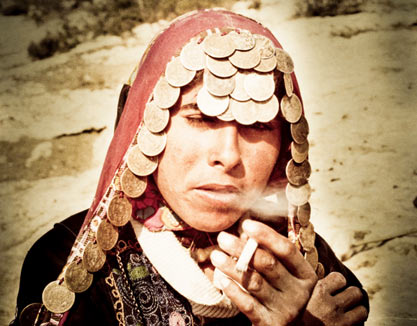

A Bedouin woman has to bend nearly to the ground when she smokes so that her veil will pull away from her face just far enough to allow her to smoke without burning it. Her hands reveal that she is not “a lazy woman”, as the Bedouin women referred to me when they saw and felt how lean were my hands and how soft their skin – all too easily get slivers and blisters from carrying out chores that a Bedouin girl-child could do daily, like collecting firewood or hauling a rope from the bottom of a well with a pail half full.

I stayed and roamed with five different Bedouin clans in the course of my research in which not even one member knew how to read or write. Yet living with them restored for me the meaning and dignity of words and terms that had been hackneyed to drivel.

The full measure of the words “drought”, “patience” and “generosity” came to life when I saw this Badawia, above, drawing water with a tin cup from a spring that yielded half a drop a minute in that seventh year of drought. This particular spring was the only water source for her family and her stranger-guest, as well as for visiting members of her clan.

The full measure of the words “drought”, “patience” and “generosity” came to life when I saw this Badawia, above, drawing water with a tin cup from a spring that yielded half a drop a minute in that seventh year of drought. This particular spring was the only water source for her family and her stranger-guest, as well as for visiting members of her clan.

It took her hours upon hours to fill her water jerrycans, then hours upon hours to carry them to her “kitchen”. And if a parched nomad happened on her way, she’d share her precious drops to quench his thirst.

The water conduit was invariably a Badawia—a Bedouin woman—like this one, transporting heavy jerrycans full of water for kilometers over rugged terrain in bare feet. Her husband as well as her other male kinfolk were the only ones wearing shoes.

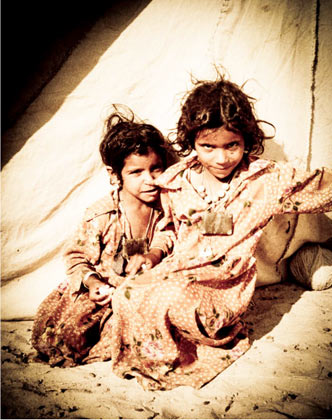

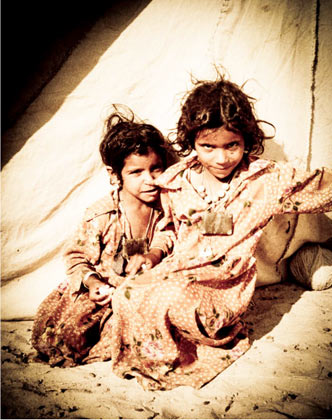

It was from a Bedouin child like this one, and the one crouching in the darkness behind me, that I learned the full meaning of the term “scraping rock bottom”.

It just so happened that during my research work, the desert regions suffered yet another year of drought—for the seventh year in succession, just as in Joseph’s time. And though longer than ever ropes dropped a pail over the lip of the waterhole, time and again the pail would come up empty. “‘For the water is trapped between the rocks at the very bottom of the well,’” according to the Bedouins by the well. “Finally, in desperation, the Badawias tied a rope around a child’s waist and slowly and carefully lowered the child into what seemed like a bottomless pit. Then they lowered a pail and moved away from the lip of the well to afford the child enough light to see. Whenever the child cried, ‘I found it, I found it,’ the pail would be pulled up, full of murky, stale water that smelled and tasted even worse than it looked. If they were not so addicted to tea, they’d probably all be shivering and sweating with malaria by now.” (Sulha)

It was also “women’s work”, as the Bedouins called it, to gather firewood for the fires at the Maq’ad—the men’s guest-receiving-place; as well as goat dung for the cooking-fire at the women’s section of the encampment.

The nomad’s kitchen.

Here, the Bedouin woman, fully veiled, is preparing supper—the one daily meal for most nomads—for which the little one is too hungry to wait.

Here, the Bedouin woman, fully veiled, is preparing supper—the one daily meal for most nomads—for which the little one is too hungry to wait.

Her kitchen counter is a torn sack spread flat on the hard, sun-baked ground, upon which she has to crouch in order to build and to refuel her stove and oven: her cooking fires—one for the rice, the other for the pitas. The jerrycan at her right and the pail on her left serve as her kitchen sink. Her cooking utensil is a shibriyya—a dagger. Rice is boiled in a chipped enamel pot. Pita is baked over a flat iron disk that looks like the top of a rusty gasoline barrel (and probably is the top of a rusty gasoline barrel).

It is impossible to keep dust and sand away from the food because of the ever-blowing desert wind and the ever-meandering goats and saluki dogs.

Even at this early age, this girl-child is so disciplined that no matter how thirsty she is, she won’t demand or nag anyone for a drop of water from the jerrycan by her side.

Even at this early age, this girl-child is so disciplined that no matter how thirsty she is, she won’t demand or nag anyone for a drop of water from the jerrycan by her side.

Her kinfolk believe that “a boy should not be disciplined as much as a girl, lest he be fearful. A girl should not be indulged as much as a boy, lest she be wilful—overly strong, refusing to do what she is told, talking back, doing things without permission. . . .

“A true real woman is a woman modest, obedient, deferential, soft-spoken, and at the same time, like a true real man, she must be strong, courageous, assert herself . . . even against her husband, if he or his blood-kin dishonour her blood-kin or herself. Or she will not be respected.” (Sulha)

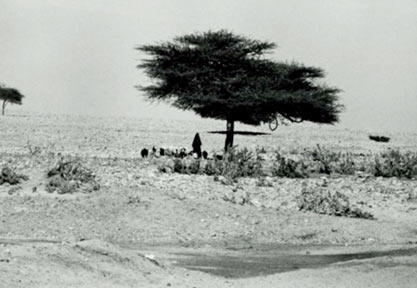

A girl, like this one—who is not yet a maiden, else her face would be veiled—is charged with shepherding the goat herds of her father’s wives. Most days she’d lead the herd to a water source not far from her clan’s encampment. But then, as the goats would devour any green blade they could find near the water source and/ or the encampment, the girls are compelled to lead the goat herd a further distance—as far as three days and nights away from their home encampment. A shepherd girl would be alone, or with a cousin, and sometimes with sisters as little as the ones in the following photograph.

A girl, like this one—who is not yet a maiden, else her face would be veiled—is charged with shepherding the goat herds of her father’s wives. Most days she’d lead the herd to a water source not far from her clan’s encampment. But then, as the goats would devour any green blade they could find near the water source and/ or the encampment, the girls are compelled to lead the goat herd a further distance—as far as three days and nights away from their home encampment. A shepherd girl would be alone, or with a cousin, and sometimes with sisters as little as the ones in the following photograph.

They’d laugh at me on the few occasions that I accompanied them, because I’d fear we were lost soon after we’d left the water source. It was beyond me how they could find their way—as if a compass had been implanted in them—in a wilderness that had no landmarks whatsoever. (This was before GPS.) What had been ingrained in them was that the desert—the Bedouins’ desert—was a place safer for a woman than a man. So highly do the Badu value a woman that “one of [their] names for woman is amarat a’beit, meaning the main pole of the tent, the pillar of the house. If a woman is violated, it is as if the house or tent has collapsed.

And even in blood-price, a woman is valued more than a man: forty camels for killing a man; one hundred and sixty camels for killing a woman; three hundred and twenty camels for killing a pregnant woman.

“Even a wealthy tribe can become impoverished if one of its sons harms a woman, even if in error. That is why women wear black, to prevent error. Even in the old days, when Badu tribes raided one another and plundered, the men would flee if too weak to drive back the attackers. But the women and children stayed. They knew that no matter how their menfolk fared, no other Badu tribe would stoop so low as even to frighten a Badawia, let alone harm her.” (Sulha)

Girls, even as young as the ones to the left, will start to learn how to tend goats: on the job, by joining a shepherdess not much older than they are, on days when the shepherdess will walk a relatively short distance: two to three hours each way from their encampment.

Girls, even as young as the ones to the left, will start to learn how to tend goats: on the job, by joining a shepherdess not much older than they are, on days when the shepherdess will walk a relatively short distance: two to three hours each way from their encampment.

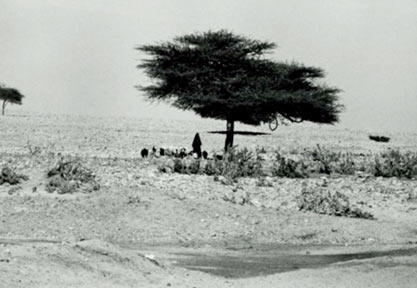

Here she is tending her mother’s goats, alone in the deserted wilderness, enjoying the cool shade offered by the thorn tree, or Acacia. Note the rope hanging on the right side of the tree. It’s with such ropes that the Bedouin women tie and fasten to the treetop their tents after they fold them and before the roam to the next water hole and/or grazing ground. Woe to anyone who stole such a tent, or anything that belonged to the Bedouins, be it tied to a tree of roaming with the goat herd – he or she would be tracked down, even if it would take five generations to catch the thief and avenge this crime.

Here she is tending her mother’s goats, alone in the deserted wilderness, enjoying the cool shade offered by the thorn tree, or Acacia. Note the rope hanging on the right side of the tree. It’s with such ropes that the Bedouin women tie and fasten to the treetop their tents after they fold them and before the roam to the next water hole and/or grazing ground. Woe to anyone who stole such a tent, or anything that belonged to the Bedouins, be it tied to a tree of roaming with the goat herd – he or she would be tracked down, even if it would take five generations to catch the thief and avenge this crime.

“It is forbidden to cut down trees like this one,” the Bedouins told me, “for they provide shade to shepherdesses and firewood for special-occasions cooking fires. And the fruit provides fodder for the flock. And if you cut down a tree like this one, you will cut down the possibility of ever living here or anywhere trees like this are growing. . . . The thorns that fall from these trees can spike right through your boots, so tread carefully,” they cautioned me, while treading there in their bare feet.

The Bedouin woman below is weaving a “welcome carpet” with long wool threads in the colours of her desert mountains, stretched tight in long neat rows. The rows are secured at each end to spikes she had hammered into the ground, weeks or perhaps months ago. Not one spike has budged, so hard was the ground in this part of the desert. Crouching as she does, so close to the ground, is such back-breaking work that she can’t weave for very long without taking a break to stretch her legs and rub her back.

It took her three years to weave her tent, using the black hair of the goats that she and her mother had raised and sheared, spinning it, rolling it onto their runners, and stringing it onto their looms.

It took her three years to weave her tent, using the black hair of the goats that she and her mother had raised and sheared, spinning it, rolling it onto their runners, and stringing it onto their looms.

Sinai dwarfs even the most courageous of “camel riders”, as the Bedouins refer to their men.

What do the Bedouins consider to be “men’s work”, one wonders, after seeing that most the time, the men just sit and talk and sip tea or coffee at their Maq’ad—the men’s guest-receiving place. At other times, they seem to take off on their camels suddenly and stealthily; disappear for days and nights, only to reappear as suddenly and stealthily as they’d disappeared.

This question loomed larger the longer I lived with the nomads and found that their “women’s work” entailed not only the raising and sustaining of their children and the sustaining of the clansmen’s lives, but also the raising and sustaining of the goat herds that “sustain the Badu way of life”; not to mention the weaving of the tents and the “welcome carpets”, and the camels’ saddlebags; as well as drawing water, carrying it, collecting firewood, building fires, cooking, cleaning . . . doing all of that in full “modest-proper” garb: ankle-length dress over dress, plus an array of shawls and heavy veil regalia, through which I could barely breathe.

It was nearly impossible for a “stranger-visitor” like me to find the answer to this and other such questions because the nomads I stayed with believed that “A Badu, the true Arab, trusts no strangers, therefore all questions from the mouths of strangers must be parried with silence or agile words. For to give information to a stranger is to hand him a shibriyya—dagger. The stranger might admire the shibriyya’s handsome handle. Or the stranger could, with its sharp edge, pierce your honour, and then your whole tribe would be bathed in shame. Such shame must be avenged . . .”

Even the Bedouin children adhered to this credo, and it was only after I stayed in one encampment for many weeks that a child revealed, “It is men’s work to gather information-power. That is why women can never be as powerful—informed—as we men are. . . . It is also men’s work to cross borders. . . .”, meaning smuggling information and goods from country to country, across very dangerous terrain, around enemy fortifications and troops. Therefore only the “best and most cunning of Badu trackers are assigned this most best and honoured and ennobling of men’s work. . . .” (It’s due to this particular men’s job, or rather the training for this job from very early age, that the Bedouin trackers are still without equal in the Sinai and even the Negev.)

“Camel riders” were also assigned to the task of fetching basic food provisions, especially when their clan was encamped at a distance of three to four days on camelback to the nearest grocery store.

This novel (Sulha) gives voice to the voiceless: to Bedouin nomadic women who share a husband in a polygamous marriage and a way of life that has endured for centuries and kept them not only veiled and out of bounds to all outsiders, but also voiceless.

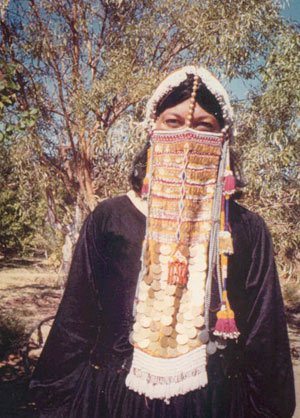

It was forbidden (in most of the Bedouin compounds where I stayed) to record a Bedouin woman’s voice; and also forbidden to photogtaph her-but not for her to photogtaph me wearing her veil, exquisitely worked by her,”so that even a person blind in both eyes can see—hear the coins of her virtue, though it covers her cheeks and chin, bespeaking of her pride, strength and endurance—and her nose—her breath, inner life, soul—and her mouth, her hunger, craving, desire, sexual charm . . .” (Sulha)

It was forbidden (in most of the Bedouin compounds where I stayed) to record a Bedouin woman’s voice; and also forbidden to photogtaph her-but not for her to photogtaph me wearing her veil, exquisitely worked by her,”so that even a person blind in both eyes can see—hear the coins of her virtue, though it covers her cheeks and chin, bespeaking of her pride, strength and endurance—and her nose—her breath, inner life, soul—and her mouth, her hunger, craving, desire, sexual charm . . .” (Sulha)

The photograph above was taken at one of the dream spot in the desert: a real oasis, not a mirage.

This cliff’s formation reminded me of the tablets on which the Ten Commandments were carved. It was the flood in Noah’s time, according to the Bedouins, that triggered a flash flood in Sinai of such force, it dragged for God only knows how many miles this boulder, arrested by these tablet-shaped peaks. And ever so precariously, it appears to be acting as a bridge, or so I like to see it:

This cliff’s formation reminded me of the tablets on which the Ten Commandments were carved. It was the flood in Noah’s time, according to the Bedouins, that triggered a flash flood in Sinai of such force, it dragged for God only knows how many miles this boulder, arrested by these tablet-shaped peaks. And ever so precariously, it appears to be acting as a bridge, or so I like to see it:

A bridge between the Dos and Don’ts A bridge to living with conflict rather than running away from it To reconciliation with the Other A bridge to Sulha

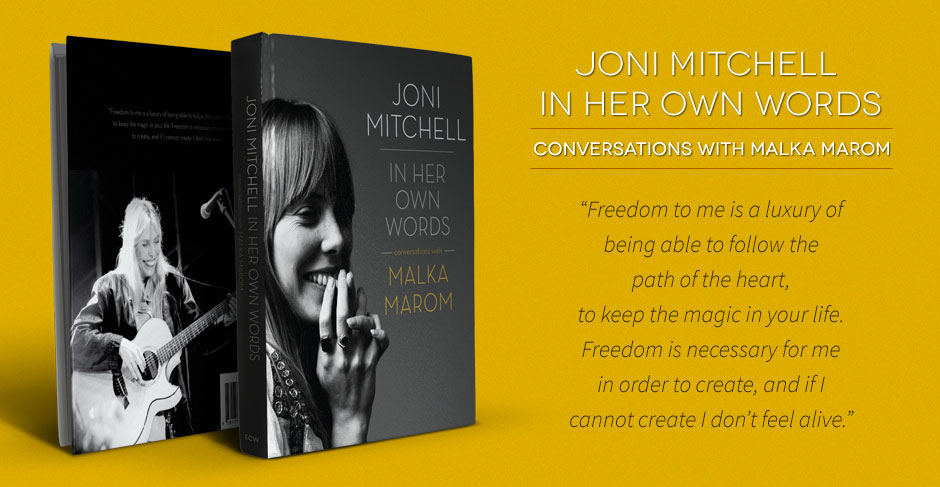

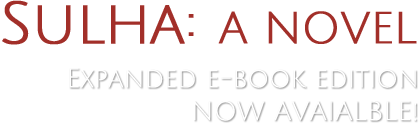

WHEN SINGER, MUSICIAN, and broadcast journalist Malka Marom had the opportunity to interview Joni Mitchell in 1973, she was eager to reconnect with the performer she’d first met late one night in 1966 at a Yorkville coffeehouse. More conversations followed over the next four decades of friendship, and it was only after Joni and Malka completed their most recent recorded interview, in 2012, that Malka discovered the heart of their discussions: the creative process.

WHEN SINGER, MUSICIAN, and broadcast journalist Malka Marom had the opportunity to interview Joni Mitchell in 1973, she was eager to reconnect with the performer she’d first met late one night in 1966 at a Yorkville coffeehouse. More conversations followed over the next four decades of friendship, and it was only after Joni and Malka completed their most recent recorded interview, in 2012, that Malka discovered the heart of their discussions: the creative process. Author Malka Marom discusses her 40 year friendship with Joni Mitchell and offers a glimpse into the creative mind of the music legend.

Author Malka Marom discusses her 40 year friendship with Joni Mitchell and offers a glimpse into the creative mind of the music legend.

but prior to it being published, she was already internationally well known. She began her career as a folksinger as part of the popular duo Malka & Joso, who were the first to bring World Music to Canada. Their recordings with Capitol EMI Records topped the bestsellers lists in Canada.

but prior to it being published, she was already internationally well known. She began her career as a folksinger as part of the popular duo Malka & Joso, who were the first to bring World Music to Canada. Their recordings with Capitol EMI Records topped the bestsellers lists in Canada. The Bedouins manner of opening their hearts and revealing their secrets—not directly but through, poetry, legends, parables and stories—inspired me to seek out my own stories, legends, parables, poetry and secrets; and to examine not only the consequences of history, but also the possibility of transcending them.

The Bedouins manner of opening their hearts and revealing their secrets—not directly but through, poetry, legends, parables and stories—inspired me to seek out my own stories, legends, parables, poetry and secrets; and to examine not only the consequences of history, but also the possibility of transcending them.

The nomads equipped not only me but also my jeep with amulets to ward off the evil eye of envy (“. . . more graves are dug by the evil envy in men’s hearts . . .” Sulha).

The nomads equipped not only me but also my jeep with amulets to ward off the evil eye of envy (“. . . more graves are dug by the evil envy in men’s hearts . . .” Sulha).

The full measure of the words “drought”, “patience” and “generosity” came to life when I saw this Badawia, above, drawing water with a tin cup from a spring that yielded half a drop a minute in that seventh year of drought. This particular spring was the only water source for her family and her stranger-guest, as well as for visiting members of her clan.

The full measure of the words “drought”, “patience” and “generosity” came to life when I saw this Badawia, above, drawing water with a tin cup from a spring that yielded half a drop a minute in that seventh year of drought. This particular spring was the only water source for her family and her stranger-guest, as well as for visiting members of her clan.

Here, the Bedouin woman, fully veiled, is preparing supper—the one daily meal for most nomads—for which the little one is too hungry to wait.

Here, the Bedouin woman, fully veiled, is preparing supper—the one daily meal for most nomads—for which the little one is too hungry to wait. Even at this early age, this girl-child is so disciplined that no matter how thirsty she is, she won’t demand or nag anyone for a drop of water from the jerrycan by her side.

Even at this early age, this girl-child is so disciplined that no matter how thirsty she is, she won’t demand or nag anyone for a drop of water from the jerrycan by her side. A girl, like this one—who is not yet a maiden, else her face would be veiled—is charged with shepherding the goat herds of her father’s wives. Most days she’d lead the herd to a water source not far from her clan’s encampment. But then, as the goats would devour any green blade they could find near the water source and/ or the encampment, the girls are compelled to lead the goat herd a further distance—as far as three days and nights away from their home encampment. A shepherd girl would be alone, or with a cousin, and sometimes with sisters as little as the ones in the following photograph.

A girl, like this one—who is not yet a maiden, else her face would be veiled—is charged with shepherding the goat herds of her father’s wives. Most days she’d lead the herd to a water source not far from her clan’s encampment. But then, as the goats would devour any green blade they could find near the water source and/ or the encampment, the girls are compelled to lead the goat herd a further distance—as far as three days and nights away from their home encampment. A shepherd girl would be alone, or with a cousin, and sometimes with sisters as little as the ones in the following photograph. Girls, even as young as the ones to the left, will start to learn how to tend goats: on the job, by joining a shepherdess not much older than they are, on days when the shepherdess will walk a relatively short distance: two to three hours each way from their encampment.

Girls, even as young as the ones to the left, will start to learn how to tend goats: on the job, by joining a shepherdess not much older than they are, on days when the shepherdess will walk a relatively short distance: two to three hours each way from their encampment. Here she is tending her mother’s goats, alone in the deserted wilderness, enjoying the cool shade offered by the thorn tree, or Acacia. Note the rope hanging on the right side of the tree. It’s with such ropes that the Bedouin women tie and fasten to the treetop their tents after they fold them and before the roam to the next water hole and/or grazing ground. Woe to anyone who stole such a tent, or anything that belonged to the Bedouins, be it tied to a tree of roaming with the goat herd – he or she would be tracked down, even if it would take five generations to catch the thief and avenge this crime.

Here she is tending her mother’s goats, alone in the deserted wilderness, enjoying the cool shade offered by the thorn tree, or Acacia. Note the rope hanging on the right side of the tree. It’s with such ropes that the Bedouin women tie and fasten to the treetop their tents after they fold them and before the roam to the next water hole and/or grazing ground. Woe to anyone who stole such a tent, or anything that belonged to the Bedouins, be it tied to a tree of roaming with the goat herd – he or she would be tracked down, even if it would take five generations to catch the thief and avenge this crime. It took her three years to weave her tent, using the black hair of the goats that she and her mother had raised and sheared, spinning it, rolling it onto their runners, and stringing it onto their looms.

It took her three years to weave her tent, using the black hair of the goats that she and her mother had raised and sheared, spinning it, rolling it onto their runners, and stringing it onto their looms.

It was forbidden (in most of the Bedouin compounds where I stayed) to record a Bedouin woman’s voice; and also forbidden to photogtaph her-but not for her to photogtaph me wearing her veil, exquisitely worked by her,”so that even a person blind in both eyes can see—hear the coins of her virtue, though it covers her cheeks and chin, bespeaking of her pride, strength and endurance—and her nose—her breath, inner life, soul—and her mouth, her hunger, craving, desire, sexual charm . . .” (Sulha)

It was forbidden (in most of the Bedouin compounds where I stayed) to record a Bedouin woman’s voice; and also forbidden to photogtaph her-but not for her to photogtaph me wearing her veil, exquisitely worked by her,”so that even a person blind in both eyes can see—hear the coins of her virtue, though it covers her cheeks and chin, bespeaking of her pride, strength and endurance—and her nose—her breath, inner life, soul—and her mouth, her hunger, craving, desire, sexual charm . . .” (Sulha) This cliff’s formation reminded me of the tablets on which the Ten Commandments were carved. It was the flood in Noah’s time, according to the Bedouins, that triggered a flash flood in Sinai of such force, it dragged for God only knows how many miles this boulder, arrested by these tablet-shaped peaks. And ever so precariously, it appears to be acting as a bridge, or so I like to see it:

This cliff’s formation reminded me of the tablets on which the Ten Commandments were carved. It was the flood in Noah’s time, according to the Bedouins, that triggered a flash flood in Sinai of such force, it dragged for God only knows how many miles this boulder, arrested by these tablet-shaped peaks. And ever so precariously, it appears to be acting as a bridge, or so I like to see it: